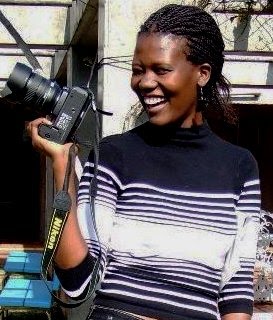

BY RITAH MWAGALE.

A baby lies in the corner of the room wrapped in pink shawl quietly nibbling onto his thumb. Unknown to him four steps away behind a maroon mackintosh curtain is his dark complexioned mother Betty lying on a black polythene (kaveera) on top of a delivery bed. Betty is being given three misoprostol tablets to control bleeding because she has just given birth to her second baby who is lying on the corner so oblivious to what is going on around him.All this is happening in Ward four which is the Labour ward of Soroti Regional Referral Hospital. On entry into the labour ward there are three old and rusty delivery beds that almost fill up the four (4)

metres long and six (6) metres wide room. The three beds are covered with green mackintoshes and separated in between by maroon mackintosh curtains.

I had the opportunity to enter this enigmatic room when I was observing five (5) of the 24 midwives from the Teso region that AMREF Safe Motherhood Programme is training in Emergency Obstetric Care and Life Saving Skills. As part of the training, the midwives from the districts of Kumi, Bukedea, Soroti, Kaberamaido and Amuria were supposed to have practical sessions in selected hospitals and health facilities to improve on their skills in conducting and managing deliveries.

When I entered the labour ward, at half past 9am, it was already in a buzz. My welcoming sight was of a light skinned woman in her twenties seated naked on the delivery bed screaming “Doctor, help me!” “Musawo (Doctor), baby is painful” and “Iam not going to ever get pregnant again!” While s she kept repeating these three statements , the midwife dressed in a pink uniform was listening and cajoling her to sip the black tea that she( the midwife) held in a blue plastic mug.

Being a first timer inside a delivery room, I was surprised and scared at the same time. Delivery rooms have always been surrounded with a lot of mystery. I had always imagined that there would be blood spilled everywhere; the smell of medicine and women being slapped around. Since I was scared to look at the screaming woman, I focused on everything in the room but her. I was pleasantly surprised to note that there was no blood spilled on the floor. Later, I learnt that this was because every time a woman vomited, defecated or had a spill of blood, it was quickly wiped away with a squeezer and water containing jik. There was also no “medicine” smell that characterises hospitals.

In addition, within that period, I learnt four things about the screaming woman. One, her name was Aisha. Two that was her first pregnancy, three she spoke only Luganda and lastly no one spoke Luganda in that room. The last discovery by default meant that I had to translate what the midwife was saying and viceversa. That was when I mustered the courage to look at Aisha. She had an expression of pain on her face and beads of sweat on her forehead. My eyes roamed downwards slowly until I saw the head of her baby trying to stick out. I quickly l

ooked away in shock but since I had caught sight of it, my eyes became more curious. By the time Aisha delivered 20 minutes later I was accustomed to the sight. I was so excited when the baby’s head finally popped out and within 30 seconds, the full baby was delivered and placed first on its mother’s stomach. I could hear Aisha scream excitedly, “

Musawo (doctor), I have given birth to a baby!” After drying the baby, the midwife held up the baby to Aisha and she became even more excited. She turned to the midwife and announced with deep pride, “Musawo, my baby is a boy!” Musawo I have given birth to a baby boy!” this she went on saying for a long time until she was led out of the delivery room.

Just as Aisha was leaving, another woman was entering the ward holding her black polythene, blue lesu (wrapper) and 4 pairs of gloves. All she said to me in Ateso was “The baby is coming!” One of the trainee midwives quickly led her to the delivery bed and within 3 minutes, I heard the baby cry. A baby boy. At 24 years, this was her fourth pregnancy. As soon as the midwife delivered her placenta, she got up and put on her blue and white skirt and blouse and sat on her delivery bed watching as the midwife examined her baby and cut his cord.

After her came two more mothers who occupied two of the three beds. With one bed left, the midwives decided to attend to those who most needed attention. Therefore as mothers continued to flock into the ward, some with their attendants in tow; the midwives first examined each one of them. Those who were found not to be in active labour were asked to go out of the room ,drink lots of cold water and walkabout until their time was up.

This action didn’t go down well with some mothers who I later learnt were carrying their first pregnancies. They therefore chose to sit outside the labour ward door and wail. One first time mother even refused to get off the delivery bed even when the midwife told her that she had five more hours to go. She just wanted to be delivered. Period.

After witnessing four deliveries, I quickly became part of the team. Being the only non medical professional in the room didn’t exempt me from performing some small tasks such as filling in the women’s bio data details on their admission and partograph forms and passing the gauze and cord ligatures that are used to tie the cords of the babies after delivery. The ward was purely manned by the midwives. It was not until one o’clock that I saw a doctor come in to examine a woman with seven months old pregnancy who he was notified, was bleeding. He also examined another pregnant woman who had pre- eclampsia ; a condition characterized by raised blood pressure, before making an exit.

From half past one o’clock, women started coming into the labour ward non-stop. Each spent no more than 15 minutes before delivery.

For the next one hour, the scenes played out in the same way…A mother came in screaming either “Baby is coming” or “I’am dying...” followed by a baby cry. Then the mothers once high pitched, pain filled voices, would change into calm and thankful ones, “ Oh my beautiful baby is born”….I got accustomed to the tempo and the sounds, that I could almost predict what sound would come next. It felt like I was listening to a secret midwife symphony. So when one woman gave birth and I didn’t hear her baby cry immediately, I felt my heart stop.

“Oh please God, let this baby be alive”, I silently prayed. The baby was white, and looked lifeless. I would have become more tensed had I not seen the calmness on the midwife’s face. Fifteen seconds later, the baby let out a cry and I felt like I have just been swept by a cool breeze on a very hot sunny day.

With all these deliveries taking place, the midwives also had to deal with the women’s relatives who from time to time kept coming into the room to check on the progress of their partners or daughters.

The labour ward also shared an entrance with another room where abnormally bleeding women were put. It was hard to control the inflow of bleeding patients and those wanting to deliver together with their attendants since all came into the room seeking attention. The midwives therefore had to balance between all these women. The influx of mothers took a toll on the supplies provided by African Medical Research Foundation (AMREF) for the participants training.

As more mothers flocked into the delivery room, there was a shortage of clean gloves. In the 6 hours, the midwives had used up 40 pairs of clean gloves. That was when I appreciated the 4 pairs of surgical gloves that each woman was told to come with because without them, it would have been impossible to conduct a safe delivery. I also couldn’t help but wonder how the staff midwives

in the hospital cope with the entire work load each day. How do they balance conducting deliveries and monitoring mothers who have given birth? I was informed that at times, the delivery room gets so congested that some women are delivered on the floor. We left the ward at 3:00pm and I realised that I had not drank nor eaten anything since I entered the delivery room.

Also, my feet hurt terribly since I had also been standing for six straight hours. I was so thirsty that I gulped down the mineral water bottle as if I had been in a marathon. I also couldn’t wait to eat, something that I had earlier on written off after seeing the first placenta being delivered.

I left Soroti labour ward, tired but the smile on the 10 mothers’ faces and the 10 innocent angelic faces that I saw being brought into this world made it all worthwhile. God bless all those midwives who each and every day bring babies into the world and ensure that women stay alive to see their babies grow. I left with a deep sense of understanding and respect for the midwives. Therefore before anyone criticises them, they should first walk the miles in their white shoes.